When you consider the fierce fighting throughout Italy during WWII between the allied forces and the retreating German army, it’s a minor miracle that so much of Italy survives intact to this day. Mortar rounds and aerial bombs could have leveled everything and so much would have been lost forever. If you haven’t done so, try to see the documentary film “The Rape of Europa” on the nazis and European art. It’s an amazing film that tells the true story of art theft in WWII by the Nazis, and the allied attempt to rescue and restore the greatest works of art.

Amazingly, the retreating german army didn’t put up a fight in Rome, and the city was spared war destruction. They retreated to Florence and Pisa in the north and prepared for battle. The allies knew that those cities were delicate time capsules of art and architecture, and they faced a difficult problem. They knew that many soldiers would lose their lives in street to street combat with the enemy hidden in the maze of medieval buildings. They also knew that they couldn’t just wipe the town away with bombs. In Florence, they made the decision to take out the train station, which was a newer structure and a critical supply line for the Nazis. This was long before laser guided precision bombs. There was no guarantee that the bombs would land where they were supposed to, but amazingly, they did. In one of the most successful bombing raids of the war, the train station was gone, and the nazis had no way to receive critical supplies.

After a year of occupation, the nazis left Florence. Before they did, they set about destroying all of the cities historic bridges over the Arno river in an attempt to slow the Allied advance. They destroyed a famous tri-arched bridge designed by Michelangelo. One bridge, called the Ponte Vecchio, survived destruction, supposedly because it was so beautiful. Today, it’s one of the most famous bridges in the world.

The Ponte Vecchio has been rebuilt many times over its history, and has been in its present state since the 1300s. It too is a tri-arched bridge, lined with shops on either side of a central corridor. In medieval times it was a center for butcher shops, and the open space of the river on either side allowed for air to control the smell. Today, the shops are all jewelry stores.  Supposedly, the term “bankrupt” was originated here, based on the words “banco rotto.” When someone couldn’t pay their debts, they would physically break (rotto) his table at the Ponte Vecchio.

Supposedly, the term “bankrupt” was originated here, based on the words “banco rotto.” When someone couldn’t pay their debts, they would physically break (rotto) his table at the Ponte Vecchio.

Thankfully, the nazis decided not to blow up the Ponte Vecchio. Instead, they leveled the historic medieval buildings on either side of it, creating a mountain of rubble blocking the bridge. While it certainly was tragic to lose large parts of the neighborhood, they have since been rebuilt and modernized. Florence certainly suffered great destruction during the war, but amazingly the greatest of buildings and historic structures made it through.

The nazis also put up a fight in nearby Pisa, which was not so lucky. Known primarily for its famous leaning tower, Pisa was a wonderfully preserved medieval city until the war, when much of it was destroyed by bombing and fire. The leaning tower and famous cathedral in the center of town survived, but not all historic structures were so lucky.

The nazis also put up a fight in nearby Pisa, which was not so lucky. Known primarily for its famous leaning tower, Pisa was a wonderfully preserved medieval city until the war, when much of it was destroyed by bombing and fire. The leaning tower and famous cathedral in the center of town survived, but not all historic structures were so lucky.

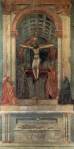

Right next to the famous leaning tower and the cathedral is a cemetery called the Camposanto. In the 12th century, knights of the fourth crusade brought back loads of soil from Golgotha, the place of Christ’s crucifixion in Jerusalem, and created a sacred burial space in Pisa. Over the centuries, the Camposanto became the cultural center of Pisa and the region. Many were buried there, and priceless Roman sarcophagi and statues, along with biblical relics, were housed there. The walls were completely decorated in immaculate frescos, and were beautiful beyond description. In short, the Camposanto was the one of the most important and priceless historical structures in all of Italy. The painting seen here shows how it looked.

Right next to the famous leaning tower and the cathedral is a cemetery called the Camposanto. In the 12th century, knights of the fourth crusade brought back loads of soil from Golgotha, the place of Christ’s crucifixion in Jerusalem, and created a sacred burial space in Pisa. Over the centuries, the Camposanto became the cultural center of Pisa and the region. Many were buried there, and priceless Roman sarcophagi and statues, along with biblical relics, were housed there. The walls were completely decorated in immaculate frescos, and were beautiful beyond description. In short, the Camposanto was the one of the most important and priceless historical structures in all of Italy. The painting seen here shows how it looked.

On July 27, 1944, a wayward Allied bombs started a fire nearby that quickly spread to the Camposanto. The wooden rafters burst into flame and melted the lead on the roof, which dripped down and completely destroyed everything inside. It was a great loss to the entire world. Along the front lines of the allied troops, cultural/art historians rushed in to assess the damage. They were devastated to find the Camposanto ruined, and set about preserving what they could. The frescos had been melted off the walls, but in some areas a faint trace of the fresco remained. Today, work still continues at the Camposanto. Though it will never be as it was, burnt fragments of the paintings have been pieced back together and can be seen on display.

Here’s a video on the Camposanto as it can be seen today- Enjoy